Food for hard thought

“If you’re unable to feed yourself healthy, delicious foods that you enjoy, you’re unable to have a productive day, you’re unable to make bigger decisions that impact long-term health outcomes for your life.” — Monique Marez, coordinator of the Pueblo Food Project

By Regan Foster

In Pueblo, one out of every five residents goes to bed hungry.

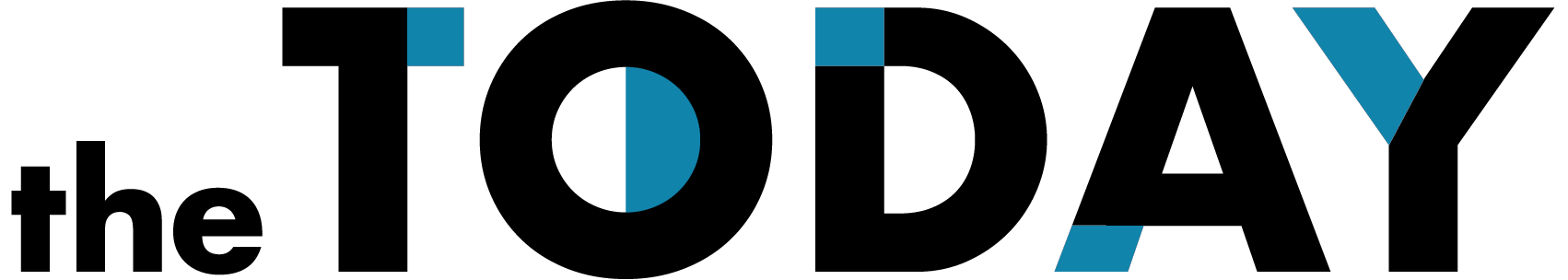

A whopping 35 percent of food produced in the United States in 2019 went unsold or uneaten.

And every two and a half minutes, the American West loses a football field worth of natural area to human development.

These problems and more were laid bare on the table Nov. 13 during the Pueblo Food Project’s inaugural Sun, Soil and Water Summit. The project–a multi-pronged initiative designed to, among other things, fill local bellies by bridging the gap between producer and consumer–hosted the two-day conference in an effort to not just identify issues facing local food chains, but explore potential solutions.

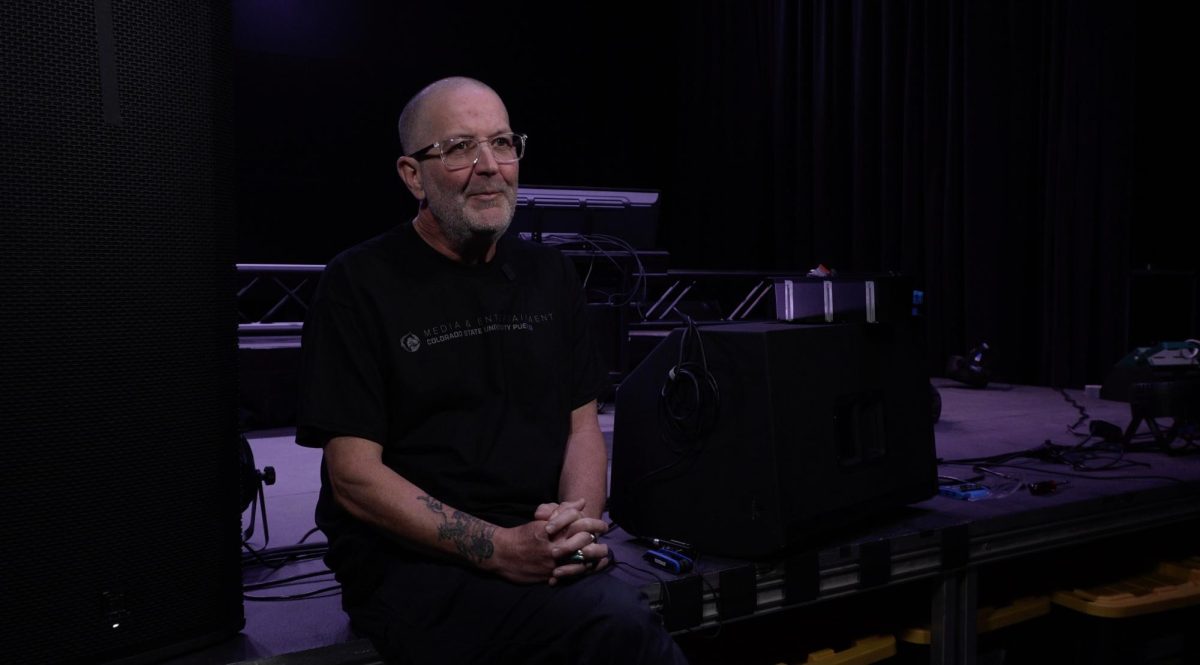

Monique Marez is the coordinator of Pueblo Food Project.

“Our hope is that this particular conference and the whole of the Pueblo Food Project leads to a more vibrant, sustainable, nutritious, equitable food system for every eater in Pueblo County,” she said. “One in five Puebloans ends their day hungry, and that’s unacceptable in our community. Along those lines Pueblo has the highest obesity rate for 18 and under in the state … by a long shot. That’s another part that is related to the food system.

“If you’re unable to feed yourself healthy, delicious foods that you enjoy, you’re unable to have a productive day, you’re unable to make bigger decisions that impact long-term health outcomes for your life.”

Attendees to the sold-out event heard from food entrepreneurs and attended seminars on diversifying food systems, local food systems and composting techniques to enhance Southern Colorado’s soil.

Matthew Garcia, CSU Pueblo assistant professor in the School of Creativity and Practice, and founder/creative director of a multi-tiered living art initiative called desertArtLAB, told audience members that indigenous plants such as cholla cactus not only repair arid soils, but they also have a deep culinary tradition in the Western U.S.

They also are stigmatized, he said.

“We all know cholla. Some of you may hate them. But that’s part of the conversation: Why do we hate our land?” Garcia said. “These things … are some of the most spectacular plants on this Earth, and they’re edible.

“Our grandparents ate cactus. We were tied to this land in ways that aren’t often explored.”

DesertArtLAB is in the throes of rebuilding a previously barren plat near downtown Pueblo, replenishing the soil using carefully selected and traditional edible plants. It’s a 30-year project on the low end, Garcia said, but its goal is to help people reconnect with the food systems around them and mitigate some of the loss of Western landscapes.

“Through our research through our endeavors, we like to ground our studies in the philosophies of the Americas,” Garcia said. “There are names for this land that precede colonization.”

David Laskarzewski, the co-director of a nonprofit partnership called UpRoot Colorado, said more than a third of the nutrient-dense food produced in this country in 2019 ended up in the landfill. He added that a single head of lettuce, tossed into a garbage bag and buried in an anaerobic environment like the dump can take between 20 and 25 years to decompose.

Food waste accounts for 8 percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse emissions — more commonly known as CO2 — on the planet, he said. That’s a lot of long-term damage from a food item that could have helped fill an empty belly, he said.

“For those of us with food access, we take it for granted,” Laskarzewski said. “And yet there are so many who go hungry.”

If this all leaves you feeling a little uncomfortable, well, good, Marez said. That’s where the solutions will be found.

“When we work together and we share resources and we celebrate successes and we collaboratively problem solve across sector, we will achieve our goals,” she said. “It’s not easy to step outside your own box, but when we do, we open things up for new possibilities.”