By Bill Redmond-Palmer

November is Native American Heritage Month, and in its honor we consider facets of education — past, present and future — as it relates to Native American, American-Indian and Alaska Native peoples.

Past

In 1634, the English Province of the Society of Jesus opened the first European-style school dedicated to the education of Native Americans in Maryland, whose purpose was, as it was described to a tribal chief, “to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race and show them the way to heaven.” Other schools followed through the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the 1800s, politicians pursued policies intended to “civilize” and assimilate Native Americans into European-American culture. They believed assimilation would allow Natives to best survive conflicts arising from European-Americans usurping their territories. The Civilization Fund Act of 1819 provided the first government funding, mostly to religious missionaries, to set up schools to educate Native children.

As tribes were pushed further west by settlers, and eventually forced onto reservations, government treaties included promises of education. These promises, bolstered by the belief that assimilation was essential, prompted the government to create American Indian Boarding Schools and Indian Day Schools on reservations. Under the management of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the system eventually included as many as 350 federally funded schools.

Charged with “guarding against the further decline and final extinction of the Indian tribes, adjoining the frontier settlements of the United States, [and] introducing among them the habits and arts of civilization,” per the Civilization Fund Act, the schools drastically altered students’ lives. Boys were forced to cut their hair short, something considered shameful to some tribes, students were assigned English names and speaking their tribal languages was a punishable offense. No expression or practice of their tribal cultures was allowed, and church attendance was mandatory.

Often children were boarded far from their families, and parents had no right to refuse attendance. Some students were allowed to visit family during the summer months, while other students were boarded year-round. Most were unable to communicate with their families while at school.

While some schools required uniforms, other children reported they were provided only the bare necessities in shoes and clothing; one set for Sunday, and another for the rest of the week. Many students were fed the same meals most every day, year-round. Students also served as cheap farm and manual labor, and corporal punishment was common at BIA schools, sometimes turning into documented abuse.

In the late 1960s the U.S. government took steps to provide tribes more self-determination, including replacing the boards of AIB schools with members of their communities. The number of schools and enrollment, however, continued to increase, and by 1973, an estimated 60,000 Native American children were enrolled in BIA schools.

In 1978 the federal government passed the Indian Child Welfare Act giving Native American parents the right to refuse their child’s placement into a school. Many of the larger schools closed by the 1990s, and by 2007 enrollment had declined to 9,500. Today, 15 boarding schools and 58 day schools still operate, though funding has greatly decreased.

Some government Indian schools in Canada made news recently, after more than 1,300 children’s graves were discovered on their grounds. This news had the unexpected benefit of making people in the U.S. more aware of the existence of these schools.

Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and the first Native American Secretary of the Interior, in response to the attention, announced a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, tasked with reviewing “the troubled legacy of federal boarding school policies.” Part of that review will attempt to assess the scope of the number and, where possible, the identities of children buried at American Indian Boarding Schools across the U.S.

It is unknown how many children may be buried on the sites of former U.S. schools; however, one researcher, Preston McBride, estimates that the number of graves to be potentially as high as 40,000.

While the intent of these schools may have been at one point nobly inspired, many Native American people consider them to have been tools of cultural genocide. In 2009, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution apologizing to Native American families for, “The forcible removal of Native children from their families to far away boarding schools where their Native practices and language were degraded and forbidden.”

If you go:

Who: Center for International Programs and Inclusive Excellence

What: An evening of traditional dance and drumming

When: 5 p.m. Tuesday

Where: Occhiato Student Center

Info: The presentation, in celebration of Native American Heritage Month, will feature information from members of the Piro-Manso-Tiwa Tribe, a Pueblo people who lived along the Rio Grande River Valley in Las Cruces, New Mexico. For more information contact Victoria Ruiz at (719) 549-2210 or [email protected].

Present

In Colorado, a unique college with a unique history exists at Fort Lewis College in Durango. Any enrolled member of an American Indian Tribal Nation or Alaska Native Village recognized by the United States government, or the child or grandchild of an enrolled member, may be eligible to attend Fort Lewis tuition free. No other institution in the U.S. has this opportunity.

This stems from the college’s unusual history. The land Fort Lewis was built on was initially a U.S. Army post, which was decommissioned in 1891. The site was then converted to house a federal off-reservation American Indian Boarding School.

In 1911, when ownership of the school and its surrounding 362 acres of land was transferred to the state of Colorado, it came with the requirement that the site house an educational institution that would not charge tuition for Native American students.

Today, about 45 percent of its students are Native American or Alaska Native, representing 185 nations, tribes and villages. Fort Lewis also hosts numerous clubs, programs and other opportunities intended to create a welcoming and nurturing space for Native American students.

The benefits offered by Fort Lewis are the exception, however, not the rule; and Native American enrollment in all Colorado higher education institutions overall is low. While none offer fully free tuition, at least two schools, Colorado State University Fort Collins and University of Colorado Boulder, have policies granting in-state tuition rates to some tribal citizens and their descendants, as well as programs to recruit and retain them.

According to the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs, there are 48 tribal nations with a history based in Colorado. Today, only two tribes remain in the state, the Ute and the Mountain Ute.

To help remedy this, the Colorado state assembly passed legislation with bipartisan support in 2021 that requires all public universities to offer in-state tuition classification to any students who are members of one of those 48 tribal nations. The Colorado Opportunity Fund aid provided to residents will also be available to those students to reduce their tuition costs.

Future

Currently, the recruitment, retention, education and program support for Native American students at Colorado State University Pueblo are limited. To help remedy this, steps are being taken to shape how CSU Pueblo interacts with tribal communities, potential Native American students and the current faculty, staff and student community.

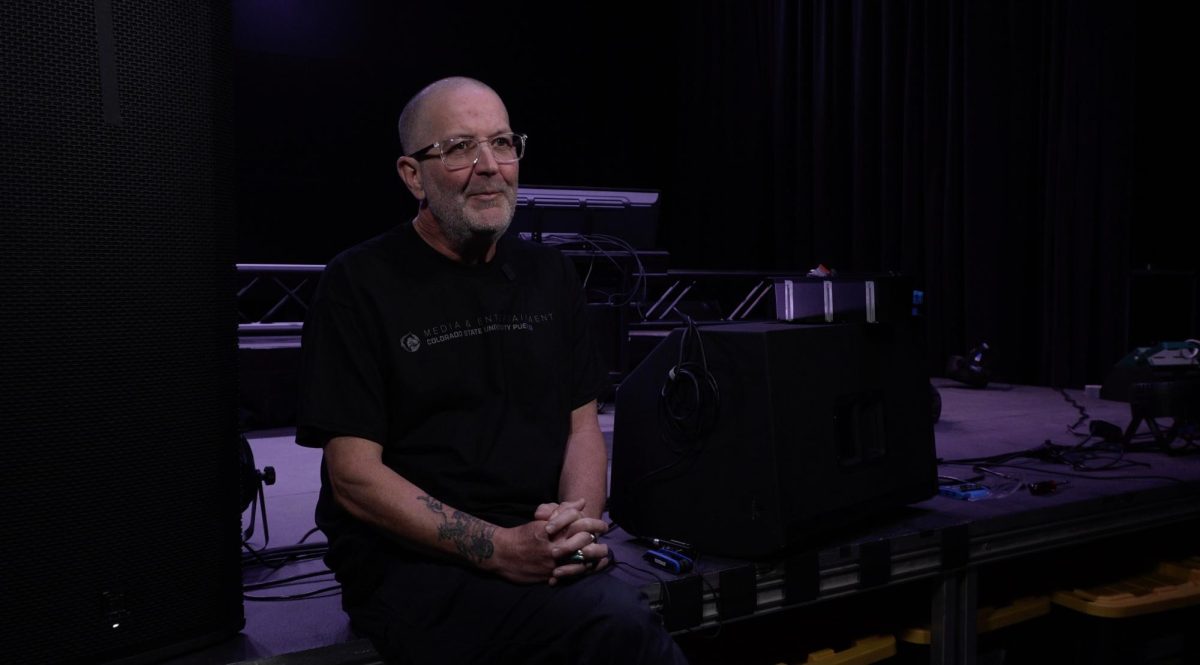

A new Land Acknowledgment Committee has been formed under the auspices of the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, a part of the Center for International Programs and Inclusive Excellence. The goal of the committee, according to Victoria Obregon, director of that office, is to develop policies and practices, “as a way for this university to honor the indigenous peoples whose lands we occupy.”

Membership on the committee is open to all interested students, staff and faculty; it meets at 4 p.m. on Thursdays in room 104 of the Occhiato Student Center.

The potential policy recommendations the committee will consider include making Native presenters feel more welcome on campus; opportunities to attract, support and make welcome Native American students; land, plant and animal stewardship; stewardship of Native American artifacts under university control; cultural educational opportunities for all students, staff and faculty; and ways to enhance existing curriculum and develop new curriculum.

For more information about the committee contact Obregon at (719) 549-2402 or [email protected].